No products in the cart.

The Four Seasons of Twin Peaks

In his first guest post, Robert J. Peterson argues that David Lynch and Mark Frost’s seminal early-90s TV series didn't have two seasons—but four.

What if I told you we’ve been watching Twin Peaks the wrong way all these years? What if I told you that David Lynch and Mark Frost’s seminal early-90s TV series didn’t have two seasons—but four? Let me explain:

For all these years, we’ve been engaging with Lynch and Frost’s series as two wildly uneven seasons—the first a perfect nine hours of suspense, surrealism, and shocking reveals, followed by a front-loaded and sprawling second season where the wheels come off. By contrast, the show can be organized into four shorter seasons,each around eight hours, each with a beginning, middle, and end, and each with their own thematic fixations and arcs.

A quote from Mark Frost spurred me to contemplate this new arrangement. In October 2014, BuzzFeed asked Frost why Showtime only ordered nine episodes. (If you recall, the new season was originally slated for nine installments. It’s since expanded to eighteen, a disparity I’ll discuss later.)

About the nine-episode length, Frost said:

“Well, if you think back about the first season, if you put the pilot together with the seven that we did, you get nine hours. It just felt like the right number. I’ve always felt the story should take as long as the story takes to tell. That’s what felt right to us.”

After reading Frost’s quote, I fixated on that nine-hour length, pondering the various ways different networks approach the concept of a “season” of television. The classic American network season runs more than twenty episodes and unspools over the course of several months, usually from September until the start of summer.

But as all of us TV nerds have learned in this, the Golden Era of Television, that’s not the only game in town. (Note: Spoilers for Mad Men and Breaking Bad appear in this graf.) Basic cable introduced us to shorter seasons—the first five seasons of HBO’s The Sopranos each ran for thirteen episodes, while its supersized sixth season ran for a more network-style twenty-one. (Though if you ask me, The Sopranos really ran for seven seasons, twelve episodes for season “six” and nine for season “seven.” As you can tell, I like reorganizing classic shows.) Other great basic-cable shows followed the “baker’s dozen” format. Mad Men’s first six seasons each ran for thirteen episodes, while its final season ran for fourteen. (I also prefer to think of Mad Men’s final season as two smaller seasons.) Breaking Bad’s first season ran a very Twin Peaks-y seven episodes, while its following four installments each ran thirteen. It’s fifth and final season ran sixteen episodes, split into two eight-episode legs across two years.

(Side note: There’s a related conversation to be had about the “BBC” model, where shows run for precisely as long as they need—The Office’s fourteen episodes and Sherlock’s twelve (so far). Both models have their virtues, but for now, I’m going to focus on the AMC model as it relates to Twin Peaks.)

Looking across these shows, we see the rise of a new phenomenon—the “midseason finale.” The midseason finale bears all the hallmarks of a standard finale—the protagonists usually find themselves in a bind or the narrative otherwise comes to a head. Mad Men and Breaking Bad both had their share of memorable midseason finales. “Waterloo” ended the first leg of Mad Men’s seventh season with such shocking twists as Bert Cooper’s death and the sale of SCD&P to McCann-Erickson. And of course, Breaking Bad’s now-legendary fifth midseason finale saw Hank Schraeder finally figure out the identity of Heisenberg.

Why am I talking about this? To soften you up to accept my thesis: that like all of the classic shows it sired, Twin Peaks followed a similar format over its twenty-nine-episode run, delivering about eight hours of television at a time, each with their own premieres and finales.

Coloquially, I refer to 12-13 episodes as the “AMC” model for season length. (And by “coloquially,” I mean “I’m the only person who uses that term because it’s a made-up thing.”) But for the sake of this essay, let me introduce a new made-up thing: the “Frost and Lynch”—or F&L—model for season length. The F&L model runs for seven to nine hours. Shorter and leaner than the AMC model, the F&L model skews more toward the BBC format, which favors the unity and symmetry of films and only calls on its TV seasons to run for precisely as long as they need to tell their stories.

So finally, let’s talk about The Four Seasons of Twin Peaks. I’ll specify how and where each season begins and ends, why I made the choices I did, all while discussing the strengths and weakness of each season—because believe me, some seasons are better than others.

Needless to say, MAJOR SPOILERS LIE AHEAD!

Season One: “Murder In A Small Town”

Pilot and episodes 1.1 through 1.7

The one unit of F&L-style seasonal storytelling you can spot with the naked eye is the first season of Twin Peaks, which also happens to be the actual, literal first season of the show. Starting with the now legendary pilot, the first season introduces us to the bizarre and byzantine world of Twin Peaks, with its interlocking network of rivalries, grudges, financial dealings, secret loves, and old hatreds—to say nothing of all the Norwegians, Brie sandwiches, black coffee, and delicious cherry pie.

Twin Peaks is many things—it’s a meditation on how evil can infest even the most good-hearted people; it’s a TV version of Blue Velvet; it’s a portrait of a small town in mourning. It’s also a cannily self-aware goof on TV itself, using the tropes and traditions of classic TV—including and especially barn-burning night-time soaps and the cornpone sitcoms of the 60s and 70s. Frost, an alum of such meat ’n’ potatoes dramas as Hill Street Blues, helped Lynch build a reliably engrossing cast of regulars, some of whom could’ve been lifted out of Dynasty or Dallas (Josie Packard, Catherine Martell, the Hornes); while others hailed more from Mayberry or Green Acres (Sheriff Truman, Andy, Lucy, Hawk). That unusual division makes for a pleasing “court and mechanicals” rift among the series regulars—a rift spanned by the show’s lead, the boundlessly kind and intuitive Agent Dale Cooper. Cooper (a stand-in of sorts for Lynch) serves many functions in the narrative—he drives the investigation into Laura Palmer’s murder, he provides key exposition—but more than anything else, he’s good. He’s decent and kind and empathetic, and in a show that’s largely about a battle between kindness and cruelty, he’s our greatest, clearest, most shining avatar for the former.

But anyway, let’s get back to season one, which unfolds over the course of nine of the most perfect hours ever seen on television. I get goosebumps when I recall some of its best moments—when the gang discovers the mysterious cabin where Laura and Ronette spent some of their harrowing final moments; when Coop asks Hawk if he believes in souls (“Several,” comes Hawk’s prescient answer).

The first season also includes some of the finest examples of what makes Twin Peaks so influential: its willingness to smuggle arthouse imagery onto mainstream television. Sometimes that imagery is a simple combination of the daft and the terrifying, such as when Waldo the parrot gets it: Perched above an exquisite arrangement of doughnuts, Waldo chillingly recites Laura’s sorry pleas before an unseen gunman silences him, spattering the bird’s blood across the table.

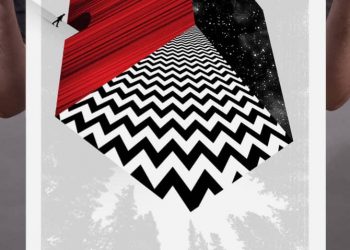

Other times that imagery is… well, this:

Among its many virtues, Twin Peaks acted as a Trojan horse for arthouse imagery, techniques, impulses, and methods. It gave David Lynch a nationwide showcase for his mastery of dream-logic—and that daring has echoed across the following decades. I’d argue with confidence that not only did Twin Peaks sire the current golden age of television, but also that it specifically paved the way for shows like The Sopranos and Mad Men, both of which traffic in dream-logic storytelling.

Season One at a Glance

Strengths: Narrative tightness, dreamy imagery, perfect introductions—and every episode is a classic.

Weaknesses: I’ve never liked how Major Briggs strikes Bobby in the pilot. It’s always felt like an early-development misstep—a flashy choice they made before they really got to know the character.

Best episode: This was a tough choice between the pilot and episode three, “Zen, or the Skill to Catch a Killer,” but episode three scores a narrow victory. From beginning to end, it’s a perfect episode, packed with unforgettable scenes—from the opening introduction of a baguette-bearing Jerry Horne to Coop’s rock-toss to the now-immortal first visit to the Black Lodge, it introduced the imagery and perfected the particular off-kilter tone and humor that made Twin Peaks a hit.

Second-best episode: I’m a huge fan of the season-one finale. It’s the only episode written and directed entirely by Mark Frost, and it shows. One of Twin Peaks’ myriad delights is the ongoing storytelling tension between its two eminent showrunners—Lynch is withholding and abstract, Frost generous and straightforward. Well, that straightforwardness makes for a rousing, headlong finale. I mean, it’s simply packed with stuff happening: the mill gets blown up, Andy shoots Jacques Renault, and of course, Coop gets shot.

Season Two: “The Investigation”

Episodes 2.1 through 2.7

My toughest choice for this essay was where to place the “second” season finale. Given that the first 15-16 episodes all bear on the revelation (and death) of Laura’s murderer, I had a few options. Does the “season” end right after her killer is revealed, in episode seven, “Lonely Souls”? Or does it end when her killer dies in episode nine, “Arbitrary Law”?

I eventually decided to make episode seven, “Lonely Souls,” the finale. Here’s why: If you were to plot the episodes of Twin Peaks on a graph where the Y-axis represented an amalgam of quality and thematic payload, you’d see several spikes, usually when Lynch and Frost dropped in to write and direct an episode. They dropped in less and less often as the series went on, turning over the major writing duties to a team that came to be dominated by Harley Peyton and Robert Engels (who was a major contributor to both the series finale and the movie, Fire Walk With Me), and an eclectic crew of directors that included television journeymen (or journeywomen) like Lesli Linka Glatter, Todd Holland, and Tim Hunter, as well as some oddballs like Diane Keaton (whose episode ain’t bad) and Uli Edel.

But the Lynch episodes carry an especial level of importance, and if we also factor the series finale into this equation, we further find that the series’ major events revolve around the activity of the BOB entity.

And on that note, let commence an aria about the Twin Peaks that could’ve been:

By now, it’s conventional wisdom that ABC screwed up the show by forcing Lynch and Frost to reveal the identity of Laura’s killer. It robbed the narrative of its momentum and revealed the execs’ fundamental misunderstanding of what Twin Peaks was—it was never a murder mystery. It was a demented and dreamy portrait of a small town. Laura Palmer’s murder was simply an initial, delicious hook to reel in the audience. In a better world, the showrunners would’ve been able to delay the revelation of Laura’s murderer until the series had run its course, saving its most dramatically satisfying reveal for the series’ final movements, much in the same manner as The Fugitive, which saved the capture of the one-armed murderer (himself referenced in Twin Peaks’ own one-armed man) for its series finale.

But here’s the thing: not even ABC could completely screw up a show this good. Happily, the revelation of Laura’s killer only raised a larger, more inscrutable question: What exactly is happening in Twin Peaks? That structure—answering one question while raising others—was forced upon Lynch and Frost, but they handled it gamely, establishing a modus operandi later imitated by shows like LOST. (Side note—LOST ain’t perfect, but damn if it isn’t the closest thing we’ve had over the years to the kind of week-to-week weirdness that Twin Peaks delivered. I rewatched it recently, and it remains one of the all-time great shows.) In any event, here’s the point of my aria: Lynch and Frost are master showrunners. When forced to solve their story’s central mystery, they deftly redirected the show’s energies into a new and larger mystery: what is BOB?

So endeth my aria. Let’s try to focus on taking about what actually happens in my proposed season two: we meet some intriguing new characters (Lenny von Dohlen’s Harold Smith, among others) and delve deeper into to the investigation of Laura’s murder. We also learn that while Laura’s murderer was technically her father, Leland (the incomparable Ray Wise), we also learn that he was under the possession of the malevolent entity BOB.

This season also sets up the following two seasons in my arrangement: Coop gets word that his old nemesis, Windom Earle, may be at large again, while Major Briggs hints that something paranormal may be afoot in the woods surrounding Twin Peaks.

Season Two at a Glance

Strengths: Momentum established in season one carries through the end of this season. We find out who killed Laura. We learn more about the entity BOB. Premiere and finale are both top-notch episodes.

Weaknesses: That “season one” magic starts to fade, but otherwise, I’d argue this season is as strong as season one.

Best episode: “Lonely Souls.”

Season Three: “Aftermath”

Episodes 2.8 through 2.14

Well, it was nice while it lasted.

My “third” season of Twin Peaks compartmentalizes all of the series’ weakest elements. Its worst storylines and worst episodes can all be found in this seven-episode stretch, which sees James ditch town for a pointless fling, Nadine succumb to retrograde amnesia, and Ben Horne become a Confederate war general. Hoo boy.

On the plus side, there are some great episodes in here. The Tim Hunter-directed ninth episode, “Arbitrary Law”—which unmasks Laura’s killer—features one of the series’ most powerful scenes—Coop cradling a dying Leland after he confesses to the crime. As the jail’s malfunctioning sprinklers rain upon them, Coop recites from the Tibetan Book of the Dead, providing Leland absolution before he dies. On the writing side, Harley Peyton and Robert Engels start to take the reigns. I have no idea if either of them emerged as defacto showrunner, but I generally dig their episodes.

As for the “third” season finale, I decided on “Double Play.” Windom Earle’s first appearance onscreen remains a strong moment, and it kicks off the action for my proposed “fourth” season.

Strengths: Although the show jumps the proverbial shark in its “third” season, it’s still got that Twin Peaks magic, which lends it incredible charm even through its weakest stretch. Gary Hershberger’s Mike, basically unseen since the pilot, gets to shine. Windom Earle’s impending entry to the fray is legitimately menacing.

Weaknesses: Too many to count.

Best episode: “Arbitrary Law.”

Season Four: “Project Blue Book”

Episodes 2.15 through 2.22

Twin Peaks was the first show I binged.

This was years before Netflix streaming, years even before Netflix’s DVD-by-mail service. I was just out of college, and although I’d seen the show’s first season (as well as the movie—don’t judge me), I’d never watched the show in its entirety. Luckily, my mom’d given me the complete series on VHS (!) for my birthday. Over the course of a week, I watched the whole series in grainy, pan-and-scan, LP glory.

Ever since that first viewing, the awesomeness of the final eight episodes has lingered with me. When I first encountered the Black Lodge, I felt sure that it’d be impossible for the showrunners to explain what it was without robbing it of its power.

Boy, was I wrong.

Over the course of eight episodes, Twin Peaks imports themes and devices from shows like The Night-Stalker and The X-Files, pitching the Black Lodge as a sort of interdimensional nexus. You can only access it from certain places, and while it’s well-nigh impossible to escape, if you do, you’re liable to pop out at any place—or any time—in the world.

Shows like Twin Peaks often straddle the line between science-fiction and fantasy until they’re forced to commit to one. LOST began as a crunchy sci-fi epic in the mode of MYST but eventually committed to contemporary fantasy in its final seasons, much to its detriment, I’d argue. But Twin Peaks gets to have its cake and eat it by treating the Black Lodge as neither magic or science, but paranormal and preternatural. Twin Peaks draws on a great many American folk myths, including an old favorite of mine, the Mothman. As the story goes, the Mothman is an extradimensional entity that supposedly menaced the town of Point Pleasnt, W.Va., in the late sixties, wreaking all manner of mind-bending havoc—delivering confusing reports about the future, teleporting people great distances, and inducing selective amnesia (or time-loss) among its victims. If you ask me, encountering the Mothman sounds a lot like a visit to the Black Lodge. (Side note, Mark Pellington’s 2002 movie The Mothman Prophecies is worth a look. It’s based on John Keel’s (supposedly) nonfiction book of the same name.)

Anyway, in its “fourth” season, Twin Peaks deepens its mythology, placing the eccentric hamlet at the center of an interdimensional superhighway. Incidentally, more of this deeper mythmaking bubbles up in the prequel movie, Fire Walk With Me, as well as its companion work, The Missing Pieces—basically ninety minutes of deleted scenes from the movie. In FWWM and The Missing Pieces, we glimpse new realms (and new citizens) of the Black Lodge, while also bearing witness to some of its temperospatial aftereffects—David Bowie’s Phillip Jeffries teleports across the world in the manner of the X-Men’s Nightcrawler, while Heather Graham’s Annie Blackburn appears to Laura Palmer to warn her of future calamity.

Strengths: An alluringly creepy, paranormal tone. The finale is one of the greatest episodes in TV history.

Weaknesses: The sharp turn into X-Files territory may not be to everyone’s liking, but it’s certainly to mine.

Best episode: “Beyond Life and Death.”

So those are my proposed four seasons of Twin Peaks. What do you think? How might you rearrange the episodes, if at all? Should someone assemble a new prequel miniseries built from FWWM and The Missing Pieces?

Also, what does the eighteen-episode revival herald in terms of storytelling? Will Lynch and Frost adhere to the F&L model, delivering two nine-episode “seasons” to us? Or have they essentially written an eighteen-hour movie that’ll unspool in a way none of us can predict?

I don’t know the answer. All I do know is I can’t wait.

I just felt a need to point out that the X-Files didn’t start broadcasting until September 1993, over two years after the final episode of Twin Peaks. I love The X-Files, but Twin Peaks didn’t import anything from it, it imported from Twin Peaks.

@Derek — thanks for the well-considered comment, and thanks for reading!

For what it’s worth, let me offer that my sentence was more figurative than literal. When I say a show imports themes from another, I’m trying to indicate what those shows have in common, not that the showrunners of one show were watching another and said, “Hey, we ought to do that.”

All the same, your comment is well-taken. Thanks for reminding me of the chronology. Add The X-Files to the long, proud list of shows sired by Twin Peaks!

Heck, there were several TP alums on X-Files, most notably David Duchovny, whom I had forgotten was on TP until I binge-watched it on Netflix…

Yep! I love to imagine that they occupy the same universe.

I don’t know if you’re a fan of FRINGE, but they specifically placed that show in the same universe as Twin Peaks!!!

When you say Twin Peaks imported themes from the X-Files, almost anyone reading that would think that the X-Files was airing at the same time as Twin Peaks, and that Twin Peaks got ideas from the X-Files.

All that being said, I do enjoy the new perspective of grouping the series into four parts. It’s not something I’d thought about before.

Finally, you mention assembling FWWM and The Missing Pieces into a miniseries. Have you watched the Q2 fan edit where the missing pieces were inserted back into FWWM using the script as a guide? Of course that makes it into one large piece, not broken up, but Q2 did a fantastic job with it. I created the day subtitles (which where again mentioned in the script) for Q2 so that they matched the brief 3 subtitles that appeared in the final theatrical film. An alternate FWWM cover art that I made was also used for the Q2 fan edit.

(Also, I know this is nitpicking, but you incorrectly say that the series on VHS was pan and scan.)

@Jared — Thanks so much for the awesome comments!

>> “All that being said, I do enjoy the new perspective of grouping the series into four parts. It’s not something I’d thought about before.”

Thanks! Glad I could offer a new look at a classic.

>> “Finally, you mention assembling FWWM and The Missing Pieces into a miniseries. Have you watched the Q2 fan edit (…)”

Nope! I’ll have to track it down—thanks for the rec!

>> “(Also, I know this is nitpicking, but you incorrectly say that the series on VHS was pan and scan.)”

Huh! Did you have my copies? Because those suckers are most certainly pan-and-scan. They’re ancient and sitting proudly on my bookshelf. Maybe it’s the “Mandela Effect.” 😉

Thanks again for reading!

Waldo was a myna bird, not a parrot.

This was a very thought-provoking article! I’ve never actively thought of dividing the seasons this way, but where you chose to end and begin new seasons really make sense to me.

@Kait — thanks for reading, and thanks for the correction! Enjoy the rewatch. I know I will!

Awesome article Robert. Thank you so much, it was a great reading. Gonna start re-watching the entire series really soon, with your truly welcomed new separation into 4 seasons in mind (well, on a piece of paper, next to my coffee and donuts!).

@Mathieu — thanks so much for the kind words, and thanks for taking time out of your life to read my article. Enjoy the rewatch! My fiancée and are planning a big one right before May 21. Can’t wait!!!

i think some of TP also takes a lot from HP Lovecraft as well.

@Delilah Agreed!

Excellent article, and a great suggestion. As someone who’s watched the whole thing through at least 15 times, I never really considered it “two seasons” or anything else in the first place – I would have binged it had it been a Netflix or similar show back in the 90s. Thinking of it in terms of seasons will definitely be a new thing now that season 3 is almost upon us…

…and the fact that season 3 is almost upon us makes me so damn happy considering I’ve been waiting for it since I was 15 years old.

@Andreas — very, very well said. It’s interesting: There’s a whole other discussion to be had about the different experience a “binger” has versus someone who watches the show while it airs. I think bingers tend to be more forgiving and more willing to take a show holistically — appreciating all of its parts, even if some of ’em ain’t so great.

By contrast, I think it’s much easier to hate on a show if you’re watching it as it airs, simply because it takes so much longer to watch it. Pursuant to that idea: I can imagine how much “worse” Twin Peaks’ second season must’ve felt at the time. IMHO, all of the weakest episodes are found in that one eight episode stretch. For fans who watched the show as it aired, that means there were at least two months when Twin Peaks was “bad.” But if you’re bingeing the show, you can blitz through those eight episodes pretty fast.

Moreover, let me offer this: One of my least favorite parts of fandom is the tendency to dismiss an entire property—movie, TV show, etc— because you didn’t like one or more parts of it. I mentioned LOST in the essay above; I could’ve written a whole side-essay about this tendency, especially w/r/t LOST. LOST is wildly uneven, and I’m not a fan of the finale, but daaaaaaaaang is it an awesome show. It’s got some of the greatest episodes in TV history, and it’s a shame that so many fans wave it away because they don’t like certain parts of it.

I’d argue that Twin Peaks has suffered the same fate, at least among some of the critical apparatus that seems convinced that the second season is a failure. One of the reasons I wrote this essay was because I wanted to find a way to say, “Hey, there are a few duds in the second season, but otherwise, it’s pretty great.”

Thanks again for reading!!!

The “dud” episodes of Twin Peaks are still at least as good as a whole lot of mainstream television nowadays, which is why I no longer have first-run TV in my house… 🙂

A thousand percent agreed. I mean—whenever I rewatch the show, I always think that. “Bad” Twin Peaks is better than 99% of most “good” television.

I’m also a huge, huge fan of Windom Earle. A great performance, plus he’s a perfect foil for Coop. And I love how they spend the whole second season building him up as this unstoppable evil—and then BOB swats him like a fly in the finale. Just awesome.

There’s a fan theory that the events of the whole series starting with Laura’s murder is just a massively convoluted plot by BOB to get Cooper to enter the Black Lodge. What do you think of this theory?

I completely disagree! I think people who watched back in the day were far more forgiving! Just looking at continuity issues, a binge watcher is much more apt to see them and think less of the production. And you had to be forgiving to stick with the show back then because time slots and days were shifting immensely. To be a fan back then you had to get beyond that, whereas now a binge watcher doesn’t even think about that.

Imagine during the last 8 episodes of the show that you had to wait over a month between episode 2.16 and 2.17 (they originally aired Feb 16 and March 28), and then between the two-episode finale and it’s previous episode (April 18 to June 10). That’s almost two months! So the last section of episodes had big gaps AND changed days of the week! To be a fan back then was tough and you had to be forgiving if you wanted to stay with it!

@Jared — well said! Thanks for reading!

Really,realy enjoyed this article. Thought provoking. But I think theres a much simpler explanation. Series One of TP was plsnbed, designed and delivered by Lynch and Frost. In Season Two, they were forced to reveal the killer too soon giving us two or three amazing visceral episodes. But then leaving them unprepared for what to do next. What you identify as Season Three,where ALL the weakest episodes lie is simply the team floundering to find a new focus,with Frost tied up with his movie ,and Lynch disillusioned.

Still some good stuff here, delivered by a stunningly talented team, but direction has been lost.

THEN they figure it out,creating the strong final nine, which gives you the feel of a renewed season. Nothing planned, just human error and weakness! Organic making it up as you go along.

.Which,of course, is the charm of TP anyway.

Think you have all the right thoughts, but the simplest explanation is best!!

PS agreed on Lost. It seems that no one even mentions it nowadays. When they do,it’s simply to dismiss it. There was genius in that show,despite flaws ( I too hated the ending!). Worth a revisit for any admirer of the fantastic…

@Michael Hatfield — thanks so much for the kind words and for your well-reasoned comment!

I’m not sure how to respond, other than to shoulder the blame for not drawing a clear enough line between the figurative and the literal in my writing — d’oh! My essay isn’t intended to argue that the showrunners literally planned out four seasons; merely that through a variety of means and circumstance, the show shakes out that way. (Note that my essay recounts the production history in some detail, including mentions of which creatives (directors and writers) came and went.)

But more important, I submit that the “four seasons” rubric can be a fun way to re-engage with an already great show.

Again, thanks for reading, and thanks for the great comment! 🙂

I like to think of Mr. Peterson’s “Season 3” as the town returning to “normal” after Laura’s murderer is revealed. The darkness returns with a vengeance in “Season 4” with Windom Earle’s quest for the Black Lodge. If anything, I would say that the chief weakness of “Season 4” is not its “turn into X-Files territory” (which I enjoy as well), but its relentless rejection of the kookiness of Twin Peaks, traits that were also absent (with good reason, obviously) from Fire Walk With Me. Hopefully the new season on Showtime will restore some of the balance between mystical strangeness and fun whimsy that Season 1 had.

Well written and argued. I’ve long thought along these lines but I’d been battling about where to drawn the line after the killer’s reveal. I think your argument holds up well.

@Murray — that means a lot coming from you, Thanks so much for reading — and glad to hear I wasn’t alone in this way of thinking!!! 🙂

Episode three is where I joined the TP watcher club. The last scene in the red Room was what did it.

@Rob — I’m with you. Episode three is just towering, a masterwork. Every time I revisit it, I discover something new. It’s replete with delights. Best of all — I love to imagine being an average TV viewer back in the day; can you imagine how many brains got melted?

It’s a show, a story, and a world well worth celebrating. What a daggum treat we get to have it back.

Thanks for reading!

I was a sophomore in high school in 1990. Even back then, my viewing preferences were considered a bit “off-center.” The fact that my parents were the ones who saw the first two episodes before I did was strange in and of itself. The show lost them by the middle of Season 2 (though my mom predicted who the killer was by the funeral scene in Episode 4), while I stayed on until the very end.

The scenes in the Red Room are, of course, the culmination of the series and I would not replace them for all the world. But having watched the series several times as an adult, I think that the “rocks and bottle” scene in Episode 3 is just as compelling, but in the opposite direction. In that scene, we see a degree of whimsy that characterizes Twin Peaks which counterpoints nicely with the darker themes of the show.

Speaking of finding something new, I just finished watching “Beyond Life and Death” yet again and I saw something that freaked me out. When Cooper is in the Black Lodge, he encounters Laura’s doppleganger, who starts screeching at him. At 39:19, a face appears for just a split second. It’s almost like a photographic negative, except it’s red. I think it’s Windom Earle’s face, but I wouldn’t swear to it.

What does it mean? I have no idea. Just more clues to the puzzle…

@Rob B — Dang! I don’t think I’d ever caught that. I’ll give it another look — thanks!

@Rob B: I think that’s a pretty cool idea! I’m not sure if it bears scrutiny, and I’m not crazy about the importance it confers on Coop as a character. Don’t get me wrong—I love Coop, but if BOB specifically targeted him, then that means Coop is somehow a more important person *cosmologically* than anyone else—it’d make him, essentially, a kind of angel.

Which—heck, that might be cool.

Thanks for reading!!!

I’m not overly interested in rearranging the structure of the show to four seasons, but I get where you’re coming from. The first season introduces everyone and establishes the mood, the second is when everything comes into motion, the third I disagree on, episode 8 – 16 are all great, and then season 4 goes deeper into a kind psychic mythology we first glimpsed in episode 2 with Cooper’s dream, and it’s a great move. I don’t see how it takes anything away from the show, it’s not just supernatural and magic, it’s collective psychic realm where our shadow selves exist imprisoned. I believe everyone in TP is of the black lodge and white lodge, I used to dislike that before I understood it and how it worked for the show rather than against it Season 1 blew my mind when I first watched it, it sucked me into a world I wanted to go on forever, and I loved Season 2…until after episode 14. Leland’s redemption and release aside, I was mortified at what had become of my favourite show. It was like a huge kick in the head, but like with the project bluebook thing, taking a step back, it makes a lot of sense in the mythology of Twin Peaks. Leland was totally inhabited by Bob, so when he was freed the demonic entity began to manifest itself in others and suddenly the town was more chaotic and less enclosed. Bob inhabited the series itself with those stupid sub plots and hijinks. I don’t think the black lodge is magical and silly, I think it’s perfectly rational from a metaphorical point-of-view and yet always mysterious and fascinating, all the more so now.

@Steven17 — Well said on all counts. Thanks for reading!

This article presents a great thoughtful argument. I would differ from you in that I would make “Arbitrary Law” the ending of season two. The philosophical/quasi-theological discussion near the end of the episode provides the audience with critical hypotheses that are sorely needed to better understand the Twin Peaks worldview, and there’s a sort-of closure there that “Lonely Souls” does not provide. There’s also still a cliffhanger with the last shot of Bob in owl form that could also have served as an unsettling, much-discussed series closer (if Twin Peaks had not continued). I could see “Lonely Souls” better as a mid-season cliffhanger, although the next “half-season” would be only two episodes long. Also, that discussion and cliffhanger in “Arbitrary Law” just do not fit well with the rest of your season three, it seems to me; they are left to just hang out there. They have far more meaning and import at the end of a season two.

And as someone who watched Twin Peaks loyally throughout its first run as a then-recent college grad (although I started watching in its summer 1990 season 1 repeats), I have to agree with Jared; I never really saw a drop in quality back then despite the conventional wisdom of the season two letdown. Rather, what I saw was that for a few episodes, the show’s already established quirky humor came into focus (welcome to me at the time, given the darkness of what we’d just experienced), and it didn’t seem long at all before Windom Earle was on the horizon. And in those interval episodes, I thought the threat of Bob was still present: since he comes to a host via fear, I thought that the unspoken question of the black widow subplot was whether James would become a conduit for Bob. If I were to divide the series into four seasons as you have done, I probably would end season 3 where you did, unless I chose it to end with Josie’s death.

@Chip: That’s really, really well said. I gave serious thought to making Arbitrary Law the second season finale, though I hadn’t assembled such a well-considered argument as yours. Thanks for sharing!

Bravo for this excellent article!

I have watched the show again recently, and I did it following your chapters – I mean I took pauses between each of the “four” “seasons”. It was great! And, still inspired by your text, I have made fan edits of the show, following your idea : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nbQHo58S25g&t=4s&list=PLi-KCUONRO9ZnGKfXIFx16SIvKpGPp-jw&index=1

I hope you’ll enjoy it.

Each video follows the order of the show (I didn’t change the order of the scenes, nor the shots). I also put dates, based on the research I have made on the internet about the chronology.

To finish, I hope my English is Ok, because I am writing to you from France.

Thanks!

@Nicholas Lincy — howdy! I already responded on Youtube, but I’ll say again: these videos are **awesome!!!!** And titling the “fifth” season “Beyond Life and Death” is totally the better call. 🙂

Thanks again for sharing, and I’m delighted you enjoyed the essay!

cool. what do you think about the new seasons music concerts? ive started thinking theyre like bookmarks for the chapters of this 18 hour movie deal because theyre not always at the end credits. in episode 8 the song comes in like 10 minutes into it, after a big (though unclear) event: the shooting of evil coop. [everyones saying bob came out of the doppelganger but we did not see that! we saw bob bubbling out but its unclear if he came out or just popped back in, which i think is possible.] then, in the after-credits-scene style, the sonofabitch sits back up jason voorhes style. fade to black and then we get taken way back in time to the trinity test, and this is DEFINITELY a different chapter in the story. my guess is that lynch/frost is doing something like the literary cut-up technique and maybe all of this needs to be watched without having to wait a week or more in between to be absorbed better. theres the seeming time discrepancies (the end credits at the rr with shelly; episode 9s dates on papers; etc) and the possible alternate universes scenes. well, youre no stranger to lynchs work, right? it wouldnt be surprising if there was even a different order in which to watch these episodes.

awesome boj done here and keep it up, old friend.

Not sure how it was in US, but the TWIN PEAKS VHS box sets were divided into 4 parts. Two VHS tapes per part.

And they were divided almost exactly as you propose from memory.

The mill was not blown up.